Restoring the little lakes of Waikato

One of the world’s rarest ecosystems can be found throughout the Waikato region.

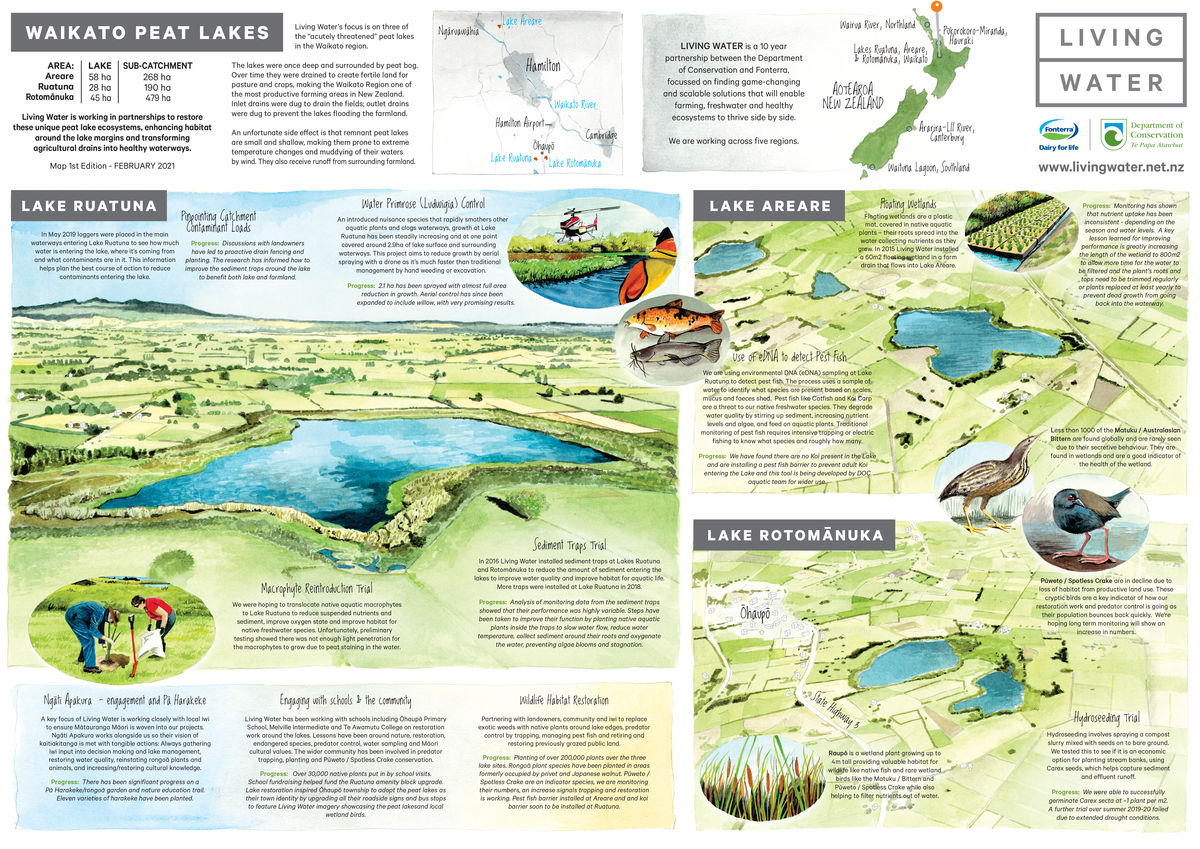

Despite being globally rare, there are 31 peat lakes located in the Waikato region. These lakes formed over thousands of years and are home to species that have adapted to their unique conditions. Classified as ‘acutely threatened’, the Waikato peat lakes are important historically, culturally and environmentally.

The lakes were once deep and surrounded by peat bog, including tall raupō, endemic rushes, and many birds, fish and insects. The lakes were lightly peat-stained and mildly acidic and held uniquely evolved wildlife. They had no natural inlets or outlets, instead absorbing water from the rain-fed peat bogs and losing it to evaporation.

Over time they were drained to create fertile land for pasture and crops, making the Waikato region one of the most productive farming areas in New Zealand. Inlet drains were dug to drain the fields and outlet drains were dug to prevent the lakes flooding the farmland. Changes to the natural drainage has made remnant peat lakes small and shallow, prone to extreme temperature changes and to muddying of their waters by wind. They also receive runoff from surrounding farmland resulting in high levels of nutrients, sediment and pathogens.

Despite these changes, unique wildlife still exists in and around the peat lakes. A report commissioned in 2015 by Living Water, a partnership between the Department of Conservation (DOC) and Fonterra, identified at least 29 indigenous plant species at Lake Ruatuna. There were seventeen native bird species observed in the catchment, including six threatened or at-risk species such as the Spotless Crake/pūweto, Australasian bittern/matuku, and dabchick/weweia. That was reason enough for Living Water to choose the Peat Lakes for freshwater projects and trials, said Sarah Yarrow, Living Water National Manager.

“Living Water worked in partnerships to restore these unique peat lake ecosystems, because we knew no single organisation had all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater”, said Yarrow. “We decided to tap into local knowledge and experience by partnering with Ngāti Apakura (mana whenua), farmers, the Lake Ruatuna users group, the regional and district councils and schools to work on the lake and its surrounds, creating a community movement that could accelerate the restoration of Lake Ruatuna.”

Lake Ruatuna is crown-owned and surrounded by farmland, 19 kilometres south of Hamilton. It’s just under two metres deep and 13 hectares in size. The area has long been special to Māori. In the 1800s, iwi including Ngāti Apakura had productive gardens throughout the current Waipā District.

Sarah Yarrow

Living Water is working in partnerships to restore these unique peat lake ecosystems, because we know no single organisation has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater

Dion Patterson

Rose Graham

- 268ha Areare sub-catchment area

- 479ha Rotomānuka sub-catchment area

- 190ha Ruatuna sub-catchment area

- 10 Fonterra dairy farms

Weaving Mātauranga Māori into the Waikato Peat Lakes restoration

Lake Ruatuna sits within the rohe of Ngāti Apakura who collaborated with Living Water to ensure the direction of work aligned with Mātauranga Māori. The partnership began with planning sessions between Ngāti Apakura and Living Water to support iwi to manage and monitor their environmental taonga. The sessions discussed cultural values and wānanga/training opportunities. Living Water supported the exercise of kaitiakitanga by Ngāti Apakura by always gathering iwi input into decision making and lake management, including restoring water quality, restoring rongoā plants, improving habitat, and increasing/restoring cultural knowledge.

The vision of Ngāti Apakura for Ruatuna is: Recognition of whakapapa aa atua, whakapapa aa tangata, whakapapa aa whenua (genealogy of the gods, people and land), guided by the relevant tikanga protocols of each hapū to maintain the inherent kaitiakitanga obligations of our tūpuna (ancestors).

One project with Ngāti Apakura was the planting of a Pā harakeke / rongoā garden and Nature Education Trail. Eleven varieties of harakeke (flax) kindly donated by local Penney Cameron from her own Pā harakeke were planted. Kuta (Eleocharis sphacelate) were planted in sediment traps and when mature can be woven into soft hats, mats, and kete. From 2024 the garden’s diverse harakeke varieties will be ready to be harvested by weavers for different projects. Yarrow said the Pā harakeke and Rongoa garden has many benefits in addition to the positive environmental outcomes.

“School students might explore the garden to learn about weaving and traditional medicine”, said Yarrow. “Weavers who have difficulty finding harakeke they need for specialised garments, such as for kete or mats and fibrous flexible cloaks, would benefit from this established source.”

Ngāti Apakura representatives developed a floating wetland made entirely of raupō (bulrush) leaves and harakeke (NZ Flax) flower stalks that was trialled in Lake Ruatuna. The design of the weaved structure was based off a mokihi (canoe) to support Carex plants long enough for them root into the edge of the lake where the raft was anchored. The mokihi exceeded expectations, Ngāti Apakura are already thinking of exciting possibilities for further designs to trial.

Landowners, council and community collaborate for change

Lake Ruatuna is surrounded by three rural lifestyle properties and four farms. Only two farms share significant boundaries with drains entering the lake. One is primarily dry stock (dairy support), while the other is a Fonterra dairy farm. Good relationships were built and lessons shared, which led to on-farm changes benefitting both the lake and farms.

In 2016 Living Water installed sediment traps at Lakes Ruatuna and Rotomānuka to reduce the amount of sediment entering the lakes from the neighbouring properties to improve water quality and habitat for aquatic life. More traps were installed at Lake Ruatuna in 2018. Analysis of monitoring data from the sediment traps showed that their performance was highly variable.

In 2019 a water quality survey report recommended planting in and around the sediment traps. It advised planting some of the tree-lined inlets with groundcover to filter surface runoff and overland flows, and planting tall sedges and grasses along unplanted drains to improve stability and to shade/cool the water. Steps were taken to improve the function of the sediment traps by planting native aquatic plants inside the traps to slow water flow, reduce water temperature, collect sediment around their roots and oxygenate the water, preventing algae blooms and stagnation. It led to other changes said Dion Patterson, Living Water Site Lead and DOC Senior Biodiversity Ranger.

“The report inspired the farmer to fence off drains, and Living Water fenced off the stream margins”, said Patterson. “Good fences are important to prevent pugging of drains by cattle, and excess nutrients and E. coli in the water. The previous fences weren’t robust enough to prevent stock getting through or were fenced only on one side.”

Partnerships with local authorities have delivered excellent outcomes for restoring the lake. The Waipa District Council (WDC) administers some of the reserve land around the lake, including the amenity block and its surrounds (DOC administers the rest). The WDC negotiated and acquired a 30-metre esplanade reserve strip beyond the pre-existing margin, for ongoing restoration of the lake. Planting with native vegetation provided valuable habitat for wildlife like rare wetland birds such as the Pūweto/Spotless Crake, while also helping to filter nutrients out of the water.

The restoration work has benefited from an innovative partnership between DOC and the Department of Corrections called ‘Good to Grow’. Teams of community service workers are facilitated by ‘Good to Grow’ at certain times of the year to work up to three days a week at the lake (or work offsite, for example making picnic tables or traps). Lake Ruatuna was one of the first ‘Good to Grow’ adopted sites. Community workers have been involved with planting, thinning established plantings, fencing, weed control, painting, and even moving 13 tonnes of shingle to upgrade tracks. This work has been valuable for restoration at Ruatuna and is ongoing.

Living Water is working in partnerships to restore these unique peat lake ecosystems, because we know no single organisation has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater

Local schools have a long history with Lake Ruatuna. Melville Intermediate School instigated building the Ruatuna amenity block in the 1990s with funding through the local Lions group, so environmental education could take place at the lake.

Living Water worked with schools including Ōhaupō Primary School, Melville Intermediate School and Te Awamutu College on restoration work around the lakes. Lessons were around nature, restoration, endangered species, predator control, water sampling and Māori cultural values. In addition, over 30,000 native plants were planted by students and staff. The local community was involved in predator trapping, planting and Pūweto / Spotless Crake conservation, and Patterson said the lake restoration has been a catalyst for other changes around the town.

“Lake restoration inspired Ōhaupō township to adopt the peat lakes as their town identity”, said Patterson. “Drive into Ōhaupō and a welcoming sign reads Home of the Peat Lakes. Three bus stops display murals of different wetland birds, a kingfisher, bittern and spotless crake painted by local artist Jeremy Shirley. The murals were revealed as they were completed with the final one being unveiled on World Wetland Day (February 2), a timely reminder of the importance of protecting our remaining wetlands. There’s a real sense of pride in the special nature of the peat lakes for Waikato and New Zealand.”

Predator prevention: ensuring native birds, fish and insects can prosper

Predator control is a vital part of the restoration of Lake Ruatuna. Without it, birdlife such as Pūweto / spotless crake wouldn’t survive. Annual Pūweto / spotless crake monitoring is gauging the positive impact of predator control and other restoration, which is yet another area where partnerships have been central to making progress, said Patterson. “The Ruatuna Users Group is primarily game bird shooters who have been involved with the lake for many years, carrying out predator control, pest plant removal and the early native planting”, said Patterson. “The community trappers are lake users, local members of the Ōhaupō community or lake neighbours. Since Living Water became involved we were able to coordinate predator trapping, with volunteers maintaining the 30 DOC traps set around the lake.”

The 2024 Pūweto monitoring recorded the second highest number of birds counted (12, one short of the best year ever). Pūweto are a great indicator of the success of a wetland restoration, because with the right conditions, populations can bounce back in just a few years because they have large clutches of up to five eggs – sometimes twice per season.

Rats, possums and stoats aren’t the only pests that need eradicating to ensure the native wildlife thrives. Catfish, goldfish, Gambusia and Rudd are all found in Lake Ruatuna. These introduced fish degrade water quality by stirring up sediment and eating native aquatic plants and/or invertebrates. Living Water managed the periodic fishing down of these pests, though luckily the (arguably) worst pest fish species is absent from the lake. That dubious honour goes to the Koi carp (Cyprinus carpo) that are native to Asia and Europe and look similar to goldfish. Their colouring is variable (gold, black, red, orange and pearly white), they have barbels at the corners of their mouth and can grow as large as 10 kg and 75 cm long. They are widespread in other parts of Waikato, Auckland and Northland regions, and in other isolated populations throughout the North Island. There are no known populations in the South Island.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) shows there are no Koi Carp in Lake Ruatuna. eDNA sampling is a rapidly developing monitoring technique that uses a sample of water to identify what species are present based on scales, mucus and faeces shed into the water. Patterson said with their destructive nature, preventing Koi carp from entering the lake is a high priority.

Koi carp are devastating to freshwater environments. They feed like a vacuum cleaner, sucking up anything in their wake and blowing out anything they don't eat. They eat insects, fish eggs, small fish, plants and almost any other organic matter. Their manic feeding stirs up the bottom of waterways, degrading water quality which destroys habitat for native fish though Koi carp can happily live in degraded water. A female Koi can lay half a million eggs at a time so preventing their spread is preferable to trying to remove a population once it has spread.

“It's important we stop Koi carp from spreading further because of the harm they cause to our freshwater ecosystems”, said Patterson. “Koi carp are very hard to eradicate so it’s much better to prevent them from entering the lake. That’s why we installed a fish barrier at the outlet from Lake Ruatuna. The barrier carries a grate that excludes fish the size of an adult Koi, in the event this fish does reach the lake.”

One pest that has made it into the lake is the Water Primrose (Ludwigia) plant, which is an introduced nuisance species that rapidly smothers other aquatic plants and clogs waterways. Growth at Lake Ruatuna had been steadily increasing and at one point covered around 2.9 hectares of lake surface and surrounding waterways. Traditional management by hand weeding or excavation was slow and costly. Aerial spraying with a drone is much faster and 2.1 hectares has been sprayed resulting in a reduction in growth. Aerial control has now expanded to include willow, with very promising results.

Patterson said transition plans were developed to hand the project over to the community when Living Water ended in 2023, so they could continue building on the momentum established.

“Living Water created an opportunity for people to get involved with their environment, and interest in Lake Ruatuna took off”, said Patterson. “There are so many active and prospective partners at Ruatuna it didn’t take a lot of effort to maintain and build on what was done.”

Looking to the future for the little lakes of Waikato

Lake Ruatuna will now be part of a larger restoration programme in the area. In November 2021 Living Water’s application to fund the Manga-o-tama Ōhaupō Peat Lakes to Waipā River Connection project secured $380,000 over two years from the Waikato River Authority.

“The goals of this project are to maintain the existing 30 hectares of planted areas, and bring willow, privet and other weeds under control, retire two hectares of farmland, and a further 7.9 kilometres of fencing installed to protect wetland and riparian waterways which will be planted up with 16,000 plants,” Patterson explained.

By the end of the first year, five farms with waterways flowing directly into the Manga-o-tama Stream and Wetland had been fenced. In all 3,228.5 metres of five-wire (electric) fencing has been installed to keep stock out of waterways. In these newly fenced areas weed control, particularly privet and willow, is being managed with spot and release spraying which extended to two further farms in the area in 2023.

Over 10,500 plants were planted at prioritised areas on five farms in the lower Manga-o-tama catchment (approximately two-thirds of the target for the project after the first year). Once the site preparation was completed 300 students from Ohaupo, Ngahinapouri, Paterangi and Puahue schools were engaged in supervised environmental planting days and planted over 4,000 plants at four of the sites.

A water quality monitoring regime was set up using Adroit real-time monitoring technology at two sites in the catchment. In addition, the manual water sampling regime has continued as well as blue/green algal water sampling for cyanobacteria.

“An exciting aspect of this project was the opportunity to use innovative technology like LandscapeDNA and real-time water quality monitoring,” said Yarrow. “LandscapeDNA uses environmental science to look at how the landscape influences the pathways and quality of water as it moves through the land.”

Traditional water quality sampling is costly and time consuming. Real-time water quality monitoring makes data easily accessible to all parties involved in the project. Having this information readily available provides evidence on the efficacy of interventions and helps people understand what happens in waterways during floods and droughts.

“Our environment wins when everyone works together,” said Yarrow. “Improved freshwater is better for wildlife, better for farming, and better for our communities. The restoration of Waikato Peat Lakes proves that local communities united with a common purpose can save these national taonga for future generations.”

Read more about this and the other work in the catchment here