Reducing sediment to restore and protect rare wetlands in Wairua

Wetlands are incredibly important for managing water quality and flow, as habitat for native species, and providing a source of food (mahinga kai) and recreation.

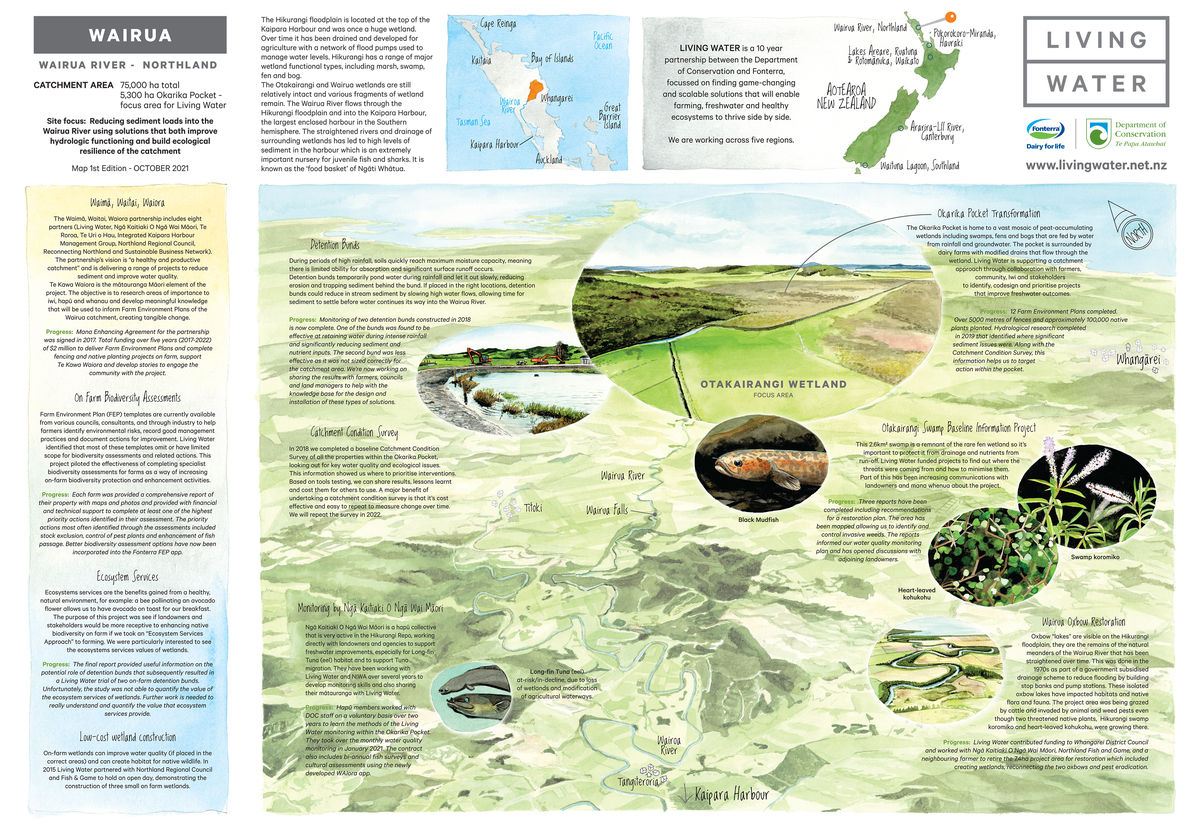

At the top of the Kaipara Harbour, northwest of Whangārei in Northland, the 75,000 hectare Hikurangi floodplain was once a huge wetland, consisting of marsh, swamp, fen and bog. Over time it was drained and developed for agriculture with a network of large flood pumps used to manage water levels. Despite the drainage and conversion to agriculture, the Otakairangi and Wairua wetlands are still relatively intact and various fragments of wetland remain across the Hikurangi.

The Wairua River flows through the Hikurangi floodplain and into the Kaipara Harbour, the largest enclosed harbour in the Southern hemisphere. The straightened rivers and drainage of surrounding wetlands deposit large amounts of sediment in the harbour which is an important nursery for juvenile fish and sharks, particularly snapper, grey mullet, flounder, mako and great white sharks. It is known as the ‘food basket’ by tangata whenua, and is a national taonga for its many ecological, cultural, historic and economic values. The mauri (life force) of the harbour, its ecological health and wellbeing is being degraded by sediment from the Wairua River network.

Sarah Yarrow

Anh Nguyen

- 75,000ha total catchment area

- 4 main types of farming (dairy, horticulture, arable, forestry)

- Fonterra dairy farms make up 36% of the catchment

- 5,300ha total Okarika sub-catchment area

George Kruger

A Collaborative effort

Living Water was part of the Waimā̄, Waitai, Waiora partnership, that collaborated to restore the mauri of the Wairoa River and its tributaries. The purpose of the five-year project (2018-2023) was to reduce sediment and bacteria levels in the Wairoa River and its tributaries by working with landowners to implement sustainable land management practices, informed by Mātauranga Māori, that improve drainage and the ecological resilience of the catchment.

The eight participants in Waimā̄, Waitai, Waiora (Living Water, Ngā Kaitiaki o Ngā Wai Māori, Te Roroa, Te Uri o Hau, Kaipara Moana Remediation (formally Integrated Kaipara Harbour Management Group), Northland Regional Council, Reconnecting Northland and Sustainable Business Network) adopted a vision for “a healthy and productive catchment” and collaborated on projects to reduce sediment and improve water quality.

Sarah Yarrow, Living Water National Manager said the project involved working with landowners to develop farm environment plans for 230 farms, incorporating sustainable land management practices and the principles of Mātauranga Māori.

“Living Water was thrilled to be working with our community partners in Waimā̄, Waitai, Waiora, as we believe there’s strength in working together and no one single organisation has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater”, said Yarrow. “Recognising the importance of the area to iwi and hapū, the partners came together under an innovative ‘Mana Enhancing Agreement’ (MEA) signed by the partnership in December 2017. This agreement placed the principle of mana at the centre of a living relationship to manage the expectations, roles and responsibilities of the partners working on this project. It provided a platform for diversity of thought and a safe place to share and work through any issues.”

With an agreement to an overall goal to reduce sediment flowing into the Kaipara Harbour, and the MEA in place, successful applications for funding projects were accepted. The five-year project (2018-2023) secured $2.5 million, including $1.25m from the government’s Freshwater Improvement Fund and $1.25m funded by project partners. The funding was used to deliver Farm Environment Plans, complete fencing and native planting projects on-farm, support Te Kawa Waiora and develop stories to engage the community with the project.

Te Kawa Waiora was the Mātauranga element of the project, to enable iwi, hapū and marae from the catchment to research issues of concern and to ensure their contribution to raising the health, wellbeing and mauri of the river was recognised.

There’s strength in working together and no one single organisation has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater

Ngā Kaitiaki o Ngā Wai Māori is a hapū collective that is very active in the Hikurangi, working directly with landowners and agencies to support freshwater improvements, especially for tuna (eel) habitat and to support tuna migration. Yarrow said Living Water worked very closely with Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Wai Māori, with both organisations sharing knowledge with each other.

“Hapū members worked with Living Water and DOC staff on a voluntary basis over two years to learn the methods of the Living Water monitoring within the Okarika Pocket, an area of surviving wetland”, said Yarrow. “As our staff passed on their scientific and technical skills, hapū members shared their Mātauranga with Living Water. It’s been an incredibly enriching process for Living Water working with the hapū collective, and proof of the value of mana enhancing agreements.”

Ngā Kaitiaki o Ngā Wai Māori took over the monthly water quality monitoring in January 2021. The contract included bi-annual fish surveys and cultural assessments using the newly developed WAIora App.

understanding the causes of water quality issues

Research and monitoring are critical for understanding the causes and locations of water quality issues. In 2018 Living Water completed a baseline Catchment Condition Survey (CCS) of all the properties in the Wairua catchment, looking for key water quality and ecological issues. A CCS collects information about a catchment via a physical inspection of properties. This field survey provides a snapshot of the catchment condition based on an assessment of stock access and vegetation along streams, soil erosion, stream structures, and significant natural areas in the catchment. Visiting properties also provides an opportunity to engage with landowners and hear directly from them about issues they’ve identified, such as seasonal flooding and erosion, or pests and invasive weeds, which may not be obvious from looking at a waterway on one particular day. The CCS is relatively inexpensive and can be repeated to measure changes over time says Yarrow.

“The Survey identifies key ecological issues in a catchment, and helps determine priority areas and activities”, says Yarrow. “Not only are they inexpensive and relatively easy to do, the field survey allows direct engagement with landowners who can share their knowledge of issues and solutions tried over time in their area of the catchment. Collectively the insights of many landowners add tremendous value to the recording of the physical and visible aspects of the catchment.”

Hapū members worked with Living Water and DOC staff on a voluntary basis over two years to learn the methods of the Living Water monitoring within the Okarika Pocket, an area of surviving wetland”, says Yarrow. “As our staff passed on their scientific and technical skills, hapū members shared their Mātauranga with Living Water. It’s been an incredibly enriching process for Living Water working with the hapū, and proof of the value of mana enhancing agreements.

UNDERSTANDING THE CAUSES OF WATER QUALITY ISSUES

Research and monitoring are critical for understanding the causes and locations of water quality issues. In 2018 Living Water completed a baseline Catchment Condition Survey (CCS) of all the properties in the Wairua catchment, looking for key water quality and ecological issues. A CCS collects information about a catchment via a physical inspection of properties. This field survey provides a snapshot of the catchment condition based on an assessment of stock access and vegetation along streams, soil erosion, stream structures, and significant natural areas in the catchment. Visiting properties also provides an opportunity to engage with landowners and hear directly from them about issues they’ve identified, such as seasonal flooding and erosion, or pests and invasive weeds, which may not be obvious from looking at a waterway on one particular day. The CCS is relatively inexpensive and can be repeated to measure changes over time said Yarrow.

“The Survey identifies key ecological issues in a catchment, and helps determine priority areas and activities”, said Yarrow. “Not only are they inexpensive and relatively easy to do, the field survey allows direct engagement with landowners who can share their knowledge of issues and solutions tried over time in their area of the catchment. Collectively the insights of many landowners add tremendous value to the recording of the physical and visible aspects of the catchment.”

Living Water returned to Wairua in 2023 to do a follow-up CCS and interviews with seven landowners to assess the state of the catchment and gather insights. The survey covered 3,518 hectares of the catchment in the focus area of the Okarika Pocket. Efforts were made to align the survey with the 2018 baseline to provide meaningful comparisons and track change.

Some of the most visible gains are the 11.4kms of new native planting along waterways, more than doubling the area recorded in the previous survey. Over 15kms of new fencing of waterways had resulted in a 7% increase in waterways where both sides exclude stock from entering.

‘These increases in native planting and stock exclusion fencing are significant gains’, said Yarrow. ‘They demonstrate an understanding and commitment by landowners to make changes that improve biodiversity and freshwater quality. Importantly they signal a change in attitude towards how we farm with nature rather than competing with it. These social changes are every bit as important as the physical changes.’

In the Okarika Pocket, continuing fencing and planting projects, and implementing catchment management approaches are the most appropriate measures for future work. Yarrow said from information gleaned in landowner interviews it appeared early community engagement and setting clear project goals are vital for the success of any programme. This involved working closely with landowners to establish objectives, identify risks and opportunities, prioritise work areas, implement actions, and maintain open communication channels.

Valuing ecosystem services is complex, especially for wetlands, and more work needs to be done to be able to use this approach to drive change

CHAMPIONING CHANGE

A challenge for Living Water was to get farmers in the catchment to view wetlands in a different way, after generations spent straightening the waterways and draining the swamps. A project was proposed to see if landowners and stakeholders would be more receptive to enhancing native biodiversity (particularly wetlands) on-farm with an ‘Ecosystem Services’ approach to farming.

‘Ecosystem Services’ are the benefits people receive from the natural environment and well-functioning ecosystems. When some people look at a wetland they may see benefits for nature, but won’t necessarily understand that people also receive benefits (referred to as services) from well-functioning ecosystems. Ecosystem services consist of provisioning services (products obtained, such as food and timber), supporting services (for example, nutrient cycling and soil formation), regulating services (including purification of water, flood control or climate control), and cultural services (such as spiritual enrichment, recreation and aesthetic experiences).

Benefits from well-functioning ecosystems are essential for providing clean water, pollinating crops, and ensuring the economic and social wellbeing of people and communities.

An advisory committee made up of representatives from Northland Regional Council, Whangarei District Council and DairyNZ helped design the trial. The ‘Ecosystem Services’ report identified the most effective farm management practices, financial costs for implementation, and the potential environmental impacts/reductions that could be achieved at a catchment scale in Wairua.

However, Yarrow said the trial found that valuing ecosystem services is complex, especially for wetlands, and more work needs to be done to be able to use this approach to drive change.

“What the trial did identify is that solutions to reduce impacts on ecosystem services (in this case reducing sediment) need to be identified, implemented and managed at a catchment scale, and should therefore be carried out by the water network manager, such as the regional or district council”, said Yarrow. “Modelling did identify that fencing of streams, soil conservation plantings and detention bunds in streams without tributaries could reduce sediment and flooding, and that gave us the encouragement we needed to proceed with trialling detention bunds.”

STRATEGICALLY PLACED AND CORRECTLY SIZED DETENTION BUNDS COULD REDUCE SEDIMENT DURING FLOODING

Northland was selected for the trial of detention bunds because during the winter months of June to August frequent and heavy rainfall saturates the ground which becomes incapable of absorbing more water. That leads to flooding and erosion, as floodwater scours sediment from the ground into waterways where the sediment covers the beds of streams damaging the freshwater ecosystem by destroying the habitat for invertebrates and clogging the gills of fish.

Living Water wanted to know whether detention bunds could reduce in-stream sediment by slowing high water flows and letting it out slowly, reducing erosion and allowing time for sediment to settle before water continued its way into the Wairua River. Yarrow said monitoring over two years including heavy rainfall showed encouraging results.

“During flooding about 70% of the excess rainfall was held behind the bund and slowly released downstream, minimising the scouring and erosion that usually occurs with floodwater and leads to sedimentation,” said Yarrow. “Sediment removal was even more successful, with about 80% of the water-borne sediment, 81% phosphorus and 45% total nitrogen dropping out behind the detention bund rather than washing downstream.”

A second detention bund trial was less effective as it was not sized correctly for the catchment area, which is an important and useful lesson to learn from the trial.

UNDERSTANDING HYDROLOGY HELPS FIND SOLUTIONS

Within the Hikurangi floodplain is the 2.6 square kilometre Otakairangi swamp, a remnant of the rare fen wetland. Living Water wanted to identify and understand the threats to this wetland, so several research projects have been completed including recommendations for a restoration plan.

The first project commissioned in 2015 recommended that Otakairangi Swamp be restored. The report recommended the destroyed populations of native rushes (Sporadanthus ferrugineus) and invertebrates (Houdinia flexilissima) be re-established and peat-forming processes restored to demonstrate what could be achieved to the community. Further reports determined the best ways of achieving the recommendations and included extensive mapping of the swamp using a drone, and understanding the hydrological functioning and resilience of the swamp.

Living Water needed to know the influence of historic and current drainage on the swamp. In 2017 an assessment of the eco-hydrological functioning of the Otakairangi Wetland was completed by Waikato University. Discussions between the report’s author and farmers led to the identification of practical solutions farmers could implement to improve the eco-hydrological processes of the wetland.

A student involved in the eco-hydrological report went on to complete a Master of Science Thesis, on the topic of determining the influence of the central drain on the condition of the wetland. The thesis identified significant points where nutrients were entering parts of the Otakairangi Swamp from two adjoining dairy farms, causing degradation of vegetation and impacting on the functioning and recovery of the ecosystem.

Yarrow said using the baseline data to inform and underpin discussions with adjoining dairy farm owners has enabled Living Water to co-design projects that will modify the drainage channels that were creating the problem.

“Sharing knowledge enabled us to have meaningful discussions with landowners about making changes to farming and land-use practices”, said Yarrow. “It has also helped design a water quality monitoring plan with equipment being installed to measure changes to sediment and nutrient levels in the central drain of Otakairangi Swamp and other waterways in the catchment. This enabled us to track the effectiveness of the projects.”

ON-FARM ACTIONS TO REDUCE SEDIMENT ENTERING THE OKARIKA POCKET

Another location of interest to Living Water was the Okarika Pocket, special peat-accumulating wetlands including swamps, fens and bogs supported mainly from rainfall and groundwater. The Okarika Pocket is a sub-catchment of the Wairua River catchment that includes the Otakairangi and Wairua River wildlife management reserves. Surrounded by dairy farms and modified by drainage, these two wetlands are by far the largest remaining in the Hikurangi Floodplain. Both reserves contain unique habitat types now rare in Northland, which make the Okarika Pocket the ideal place to observe and measure changes in water quality resulting from freshwater biodiversity improvement projects and changes to farm management practices.

Hydrological research completed in 2019 identified where significant sediment issues were located. Along with the Catchment Condition Survey, this information helped target action within the pocket. Yarrows said Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Wai Māori and Northland Regional Council helped determined where in the Okarika Pocket to concentrate efforts.

“Our focus was on the surrounding dairy farms with modified drains flowing through the wetland”, said Yarrow. “Living Water supported a catchment approach through collaboration with farmers, community, Iwi, hapū and stakeholders to identify, codesign and prioritise projects that improved freshwater outcomes. All Fonterra farms in the catchment have Farm Environment plans. Over 5km of fences and approximately 100,000 native plants were planted.

One of the greatest outcomes of working in the Okarika Pocket has been the behavioural changes and ability to connect restoration work happening on-farm with restoration work happening on public conservation land. “There has been significant changes in attitudes towards the Okarika pocket and wetlands in general, this shift means the value of environmental action is now understood and there’s a collective vision for the future of the wetland” says Yarrow.

Shared responsibility has built momentum and community connection, ensuring the longevity of the mahi beyond the 10 years of Living Water. Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Wai Māori, are looking at taking lessons learnt from the project to the Otonga Pocket, another area of importance to hapū in the Hikurangi Repo, with an ambitious plan to purchase and retire significant land areas and return this to wetland

RECONNECTING OXBOW LAKES WITH WETLANDS

Visible along the Wairua River catchment are ‘oxbow lakes’, the remains of river meanders. The meanders were blocked off in the mid-late 20th century as part of a large-scale government subsidised drainage scheme. The reasoning was that straightening waterways, building stop banks and installing pump stations would quickly drain flood waters from farms. However, the drainage works disconnected the oxbow lakes from water flows disrupting habitats and adversely affecting aquatic flora and fauna, including two threatened native plant species: the Hikurangi swamp koromiko and heart-leaved kohukohu.

Living Water contributed funding to Whangarei District Council and worked with Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Wai Māori, Northland Fish & Game, and a neighbouring farmer to retire the 7.4 hectare project area that included two oxbow lakes. The restoration project included reconnecting the oxbows to create wetlands and improve the mudfish habitat, stock-proof fencing, and plant and animal pest eradication.

With so much of Living Water’s work in Wairua relating to wetlands, Yarrows said the decision was made to provide a workshop and demonstrations of how to construct a low-cost wetland.

“It’s estimated 90% of New Zealand’s wetlands have been drained so we thought it was important to protect and enhance remaining wetlands and construct new wetlands in suitable areas on-farm”, said Yarrow. “In 2015 we partnered with Northland Regional Council and Northland Fish & Game to hold a one-day workshop on how to construct a low-cost wetland. The workshop covered the benefits of wetlands, practical advice on selecting the best type of wetland, information on construction regulations and an on-farm demonstration of construction of three small wetlands.”

THE FUTURE OF FARMING WILL BE DIFFERENT

The restoration of wetlands within the Wairua River catchment contributes to the improvement of water quality and the reduction of sediment in the waterways. Other Living Water projects such as the detention bunds provided an opportunity to trial small-scale interventions to determine if they could be successfully scaled up and used throughout the catchment. Fencing to exclude stock from waterways, and planting along waterways all contributed to improve water outcomes. Yarrow said decades spent draining the wetlands have created problems that can only be solved by restoring the wetlands to their natural ecological functions.

“Living Water has significantly contributed to the shared understanding of the ecological importance of the repo and well as it’s hydrological function.” Said Yarrow. “The changes in attitudes to restoring the natural functioning of the wetlands is proof that this is as much a people problem as it is an ecological problem, we need to put people at the heart of the problem solving.”

Though Living Water completed its trials and demonstration projects in 2023, many of the benefits of the projects will be sustained and expanded in future years. By engaging and collaborating with community organisations within the Wairua River catchment and Northland area, Living Water inspired local people to take ownership of their rare and special wetland environment. Equipped with the required knowledge and skills, local people and community organisations are ensuring the goal of achieving reduced sediment and improved water quality in the Wairua River catchment becomes reality.

Read more about this and the other work in the catchment here